To what extent is modifying Roald Dahl’s books allowed

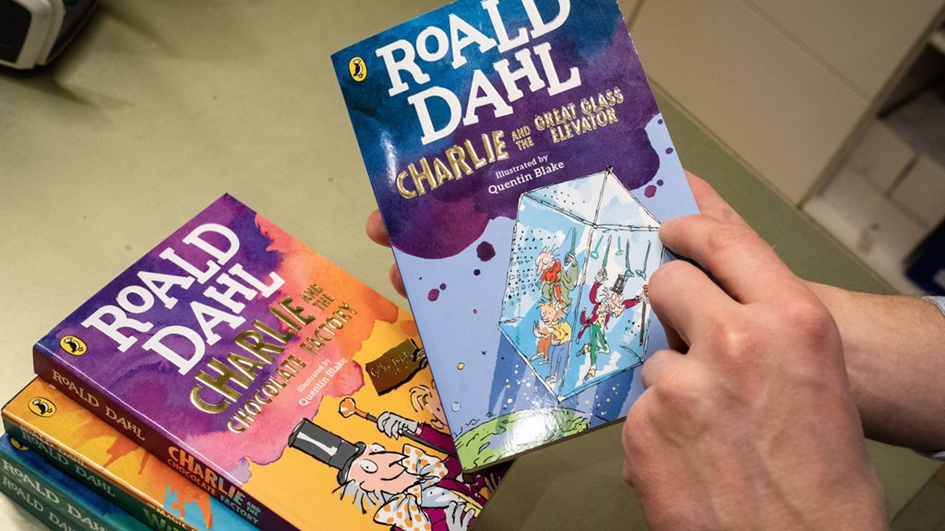

Roald Dahl died almost 35 years ago. But his books are as popular as ever, both with children and their (reading) parents. More than 300 million copies have been sold worldwide. Early this year (2023), discussion erupted following the announcement by the British publisher of the Roald Dahl books, Puffin, and the Roald Dahl Story Collection that the Roald Dahl books were being adapted ‘to the times’. Several hundred changes were made. For example, the word ‘fat’ has been replaced by ‘enormous’, and to the explanation in the book The Witches that witches wear wigs but are actually bald, it has been added that there are a ‘There are plenty of reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.’

No, there is certainly nothing wrong with that, but is that why this kind of text should be adapted? And is that allowed?

The announced changes have created a storm of criticism. And the question is whether these kinds of changes, which surely go a long way beyond a single adjustment ‘to time’, are permissible.

Copyright: exploitation rights and moral rights

Creators of (short for) creative works are automatically entitled to copyright. Copyright consists of two different types of rights:

- Exploitation rights

- Moral rights

Exploitation rights – normally referred to as ‘copyright’ – include the right the author/right holder has to publish and reproduce his/her work. These rights can be transferred by the author to another party and sometimes, by virtue of a legal rule, they already belong to another party, for example to the employer rather than the employee who created a work. The right holder can prohibit anyone else from performing these acts.

Moral rights

Unlike exploitation rights, moral rights cannot be transferred. This is because these rights are based on the personal link between the author and his work. The moral rights therefore remain attached to the author, even if the exploitation rights are transferred to another person. However, the author can waive some moral rights.

There are several categories of moral rights that can be invoked by the author. The Dutch Copyright Act (Article 25) includes, in brief, the following:

- the right of attribution

- the right to oppose changes to the work, unless that would be unreasonable

- the right to oppose the deformation, mutilation or other impairment of the work, if this could damage the honour or name or value of the author.

This is a non-exhaustive list. Other moral rights can therefore be claimed if necessary. In the UK – Roald Dahl’s home country – moral rights are also enshrined in law. The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has a chapter devoted to so-called ‘Moral Rights’ that are similar to the Dutch moral rights.

Moral rights after author’s death

In any case, moral rights expire (in the Netherlands and the UK) at the same time as exploitation rights expire. But what happens if the author dies? Since moral rights are about protecting the author’s personal interests, it is logical that they cease to exist at the time of the author’s death. But that need not be the case.

The main rule in the Netherlands is that moral rights do not inherit and therefore expire on the death of the author, unless…

… the author designates someone by will or codicil. This can be a person, but also, for example, a foundation. However, this does require action on the part of the author. Without that, the moral rights will expire. So it may well be that a famous author or painter did not designate someone in time to guard these rights.

In the UK, this works slightly different. After the death of the author, the following applies:

(a) the right passes to such person as he may by testamentary disposition specifically direct,

(b) if there is no such direction but the copyright in the work in question forms part of his estate, the right passes to the person to whom the copyright passes, and

(c) if or to the extent that the right does not pass under paragraph (a) or (b) it is exercisable by his personal representatives.

In other words, the rights pass to the person designated by will, or they pass to the next-of-kin of the copyright (i.e. the exploitation rights), or – if the previous two options do not apply – the rights can be exercised by the personal representatives. Logically, the representative(s) will (have to) consider the interests of the author. Thus, changes cannot be made just like that, but only if it is plausible that the author would have consented to those changes.

The moral rights of Roald Dahl

Roald Dahl’s moral rights were bequeathed to whoever he also left the copyrights to, according to sources his last love Liccy, after which the rights were managed and operated for years by The Roald Dahl Story Company, which sold the rights to Netflix in 2021.

It is very questionable whether the publisher of his books could have decided to rewrite texts in the books in the way that has now happened. According to The Roald Dahl Story Company, these are only “minor and deliberate adjustments”, but it is a long list. Roald Dahl was not known for being willing to make many adjustments. When it comes to the single adaptation of words that are now no longer used, or that really can’t be done (as was the case with the word ‘negro king’ in the books of Pippi Longstocking), there will be little to worry about. But in the case of the Roald Dahl books, it is more than old fashioned words or words that ‘really can’t be accepted any more’. The word ‘stupid’ or ‘fat’ does not fall into that category, in my opinion. And against a change like the one in the book ‘The Witches’, Roald Dahl would have been able to exercise his right to oppose without question. So the changes do not seem to be in the spirit of Roald Dahl. One could perhaps even speak of an encroachment on his work affecting his honour, name or value.

It seems that the publisher did take notice of all the criticism. It has now been announced that the original version of the books will also remain for sale. Thankfully.